I completed my MSc Counselling and Psychotherapy – Contemporary Creative Approaches in August 2023 with a research project called Othering Me, Othering You – My Living Experience of Internalised Patriarchy. I’m going to share the following sections from my dissertation in this post: definition of terms, introduction, and conclusion. If you’d like me to send you the dissertation or have a conversation about setting up creative workshops to uncover hidden biases with compassion, please email me.

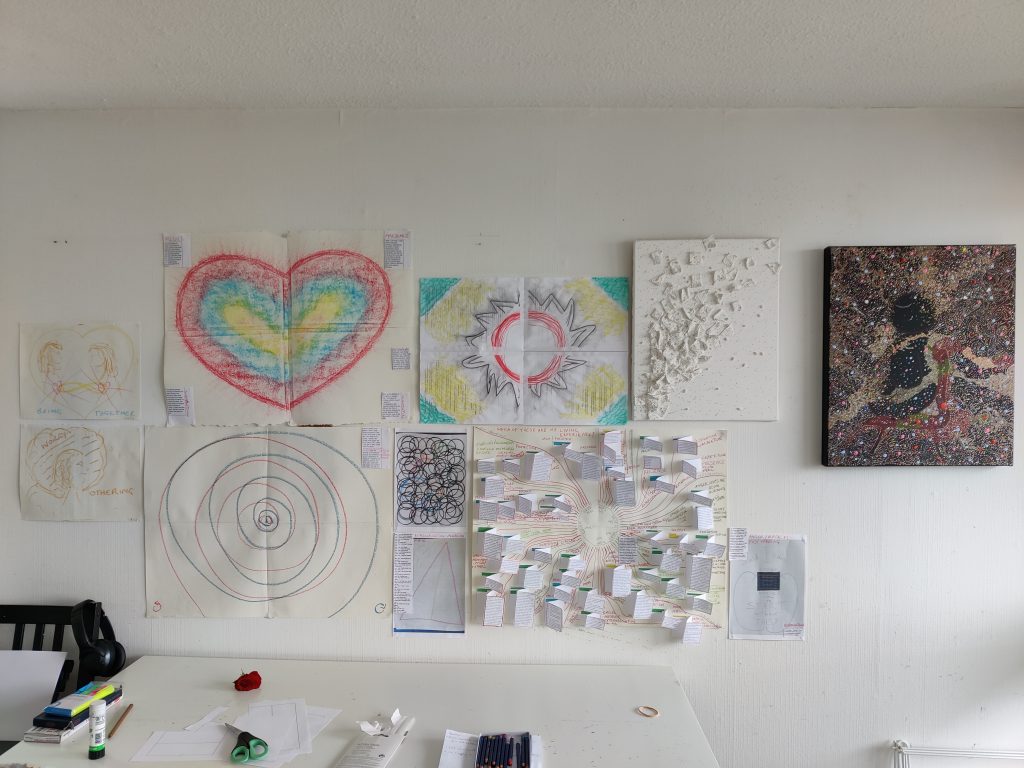

Some of my creative outputs from my research that I analysed for themes

Definition of Terms

Patriarchal Oppression

In her essay in which she gives a new definition to patriarchy, Christ (2016: 215) states ‘patriarchy literally means rule of the fathers or the father principle and is generally understood to mean a society in which power is held by males or by elite males and where power is passed from father to son.’ In other words, patriarchy is thought to be related to male domination over females. However, Christ (2016) identifies patriarchy as a complex system of oppression that comes from the historical control of women, private property and war. She highlights the importance of the links between these things as giving rise to a series of current norms that promote the white, heterosexual, wealthy male as having the most power in Western civilisations at least.

I would add cisgender, able, and anything else that is currently seen as a normal way of living or being to the series of norms. Although the idea of normal is archaic and a myth, and there is potential for norms to change over time, norms are very much part of present day Western cultures (Mooney, 2019; Mooney 2021). For example, Mooney (2021) suggests, in his presentation to teachers, there is a narrow band of skills inherent in the label ‘smart’ in academia. Those who find these skills difficult – e.g. people with Dyslexia or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder – may need accommodations, such as more time to complete tasks, and may be labelled lazy, for example, which can feel psychologically wounding (Mooney, 2021). People deemed not to fit into the norms of patriarchy are vulnerable to marginalisation at least, and violence or death at most (Butler, 2004; Hardy, 2013; Szymanski, Dunn and Ikizler, 2014; Puckett et al, 2019).

Microaggressions

Sue et al (2007: 271) give a clear description of racial microaggressions as ‘brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral [sic], or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional’. Turner (2020) shares personal examples of experiencing racial microaggressions from a white client who often did not pay on time or pushed time boundaries. In a different vein, Reyes et al (2022) share studies on how counsellors’ assumptions about clients’ sexual identities could show up as microaggressions – for example, a counsellor might assume that a client’s sexuality is the root cause of their problems. Sue et al’s (2007) concise description of racial microaggressions can be applied to all kinds of patriarchal oppressions – for example, gender, race, ability, religion, transgender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, and so on.

Introduction

Background

Since the 1960s feminist psychotherapists have been linking hidden biases and assumptions to patriarchal norms (Hogan, 1997; Butler, 2004). These norms are linked to social constructions, such as gender or race, that promote wealthy, heterosexual, white, able males as better than, or having more advantages than, all others (Butler, 2004; Roughgarden, 2014; Ananthaswamy and Douglas, 2018; Aydin et al, 2019). People deemed not to fit into the norms of patriarchy are vulnerable to discrimination (Butler, 2004; Hardy, 2013; Szymanski, Dunn and Ikizler, 2014; Puckett et al, 2019). Discrimination seems to be systemic by nature (Szymanski, Dunn and Ikizler, 2014; LiVecchi and Obasaju, 2018; Turner, 2020; Morgan, 2021; Shivers, Farago and Gal-Szabo, 2021; Beazley, 2022; Catlett, 2022; Chin, Hughes and Miller, 2022; Drustrup et al, 2022; Fripp and Adam, 2022; Mollitt, 2022; Reyes et al, 2022), which suggests that anyone could hold hidden biases. Research shows psychotherapists who act out their hidden biases and assumptions as microaggressions can negatively affect the efficacy of therapeutic relationships (Campbell and Abra Gaga, 1997; Whiting, Nebeker and Fife, 2005; LiVecchi and Obasaju, 2018).

Aims and Objectives

This study will look at my living experience of othering people different from me. My research question began as: what is the experience of internalised patriarchy for a trainee psychotherapist? During the research I changed the question to: what is my experience of othering people different from me? The aim has remained the same: to uncover my hidden biases and assumptions so that I can work safely with clients. I also hope to provide inspiration to other psychotherapists, and people from other professions, to uncover their hidden biases.

Rationale

Hidden assumptions and biases can cause harm in therapeutic relationships (Campbell and Abra Gaga, 1997; Whiting, Nebeker and Fife, 2005; LiVecchi and Obasaju, 2018), and it feels important to me, as a trainee psychotherapist, to mitigate against harm. As a person who has experienced discrimination, I am aware of the impact it can have – shame, stigmatisation and a lack of impetus to reach out for help, for example. The intersections where I have experienced discrimination or potential for discrimination occur around being female, fluid sexuality, awaiting assessment for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder / Autism Spectrum Condition diagnosis, spirituality not tied to any major religion, experience of poverty, experience of sexual, physical and emotional abuse in childhood, and experience of complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder – there are more but it would be overwhelming to list it all. Importantly, I do not have to deal with the additional impacts of discrimination around race, transgender, physical disability or religion, to name just four – I imagine I would be exhausted if I experienced daily microaggressions in connection with these too. However, I may, due to the systemic nature of patriarchal norms, have hidden biases and assumptions relating to these in addition to the ones that already affect me – for example, sexism, heterosexism, and ableism. If I can get a sense of my living experience of them, I may be able to stop them from negatively affecting me and my clients.

When healthcare professionals are unaware of their hidden biases and assumptions, they may inadvertently act out microaggressions towards marginalised populations (Campbell and Abra Gaga, 1997; Szymanski, Dunn and Ikizler, 2014; LiVecchi and Obasaju, 2018; Shivers, 2021; Catlett, 2022; Mollitt, 2022; Reyes et al, 2022) – for example, talking in a condescending manner or assuming someone can afford to travel a short distance to get treatment. People who regularly experience impacts of discrimination in daily life face further psychological distress when they are discriminated against by people in helping professions (Campbell and Abra Gaga, 1997; Budge and Moradi, 2018; Turner 2020; Valdez, 2021; Baker et al, 2022). Given that the World Health Organisation (2021) highlights marginalisation as a factor mediating for ‘mental disorders’, such as depression and anxiety, it is especially important that people working in mental health care do not add further discriminatory impacts to marginalised populations. Therefore, it is ethically important for psychotherapists to make themselves aware of their biases and assumptions (BACP, 2018).

How I Conducted This Study

I used heuristic inquiry as my methodology, and I limited my data collection to six self-led creative workshops during the first two stages within the heuristic process – initial engagement and immersion.

Conclusion

The aim of this research was to uncover my hidden biases and assumptions so as to not act out microaggressions towards psychotherapy clients. Using a heuristic process and a series of self-led, intuitive, creative workshops, I wanted to get a sense of my living experience of othering. Although some literature does go into the impacts of othering, there was not a strong sense of the experience of it.

My data revealed othering as a tangled mess of the past affecting the present, with fight, flight, and, sometimes, freeze emotional reactivity going on. Additionally, my othering of people different from me tended to be caught up in me othering myself at the same time. All of this was connected to unprocessed childhood trauma and sexual abuse, which was fed into by the wider context of the patriarchal oppression of sexism.

Despite othering the spiritual aspect of myself, it was this with its intuitive urges to move, be still, draw or write that led to me noticing the visceral sensations of othering. I now have a strong bodily sense to clue me in when othering is happening so that I can pause, and notice it. The ability of this part of me to pause and notice has allowed the emergence of exiled, traumatised parts of me to externalise and express themselves, receiving validation and compassion, and feeling calmer in the process. However, writing this paper has brought awareness of more traumatised parts. Therefore, the creative workshops devised for this research will become a regular part of my self-care and self-development.

Limitations of Study

It is possible I may have missed some biases because the situations that arose in the creative workshops did not allow for them – for example, racism or religion. However, given my desire to report honestly, if they had occurred it is unlikely that disavowal would have happened. This research was conducted solely by me, and so bias could have occurred during data collection and data analysis. I have included as much data as possible in the appendices and documented the process rigorously to minimise the risk of this.

Implications for Practice

Using creative methods can provide insights into hidden biases and assumptions, making it easier to accept them as they arise. This research suggests there could be links between unprocessed trauma and othering, and patriarchal oppressions present in societal systems, cultural products and othering / trauma. Therefore it is important to bear in mind, with compassion and empathy, the effects of cultural contexts on ourselves as professionals, our colleagues, and our clients.

Recommendations for Further Research

Future research could involve others accessing their hidden biases and assumptions in order to compare and contrast results. For example, are the mechanisms of othering the same or different? Currently, as Drustrup et al (2022) point out, it can feel shameful for some people to approach their hidden biases, so more studies that show an open minded attitude to hidden bias hunting could make it more acceptable. With regard to the open, intuitive nature of the creative workshops, it would be interesting to see what happens with an intention of finding a specific patriarchal oppression, for example, racism.

If you would like a full copy of the dissertation, or would like to have a conversation about setting up creative workshops to uncover hidden biases with compassion, please email me.